If you’ve read my previous blog post you’ll know that this breathtaking (literally!) Bolivian city was once one of the richest in all of the Americas. Back in 1544 a local Inca made a discovery that would shape Potosí’s future. He found silver.

In fact there was enough silver inside Mount Potoji (now known simply as Cerro Rico – rich hill) to – figuratively – build a bridge between Potosi and Madrid. During the colonial reign millions of indigenous and African labourers worked, ate, slept, and died down the Potosí mines.

The mountain is still being mined today but only for the lead and zinc that remain; the city is now merely a shadow of its former wealth and grandeur.

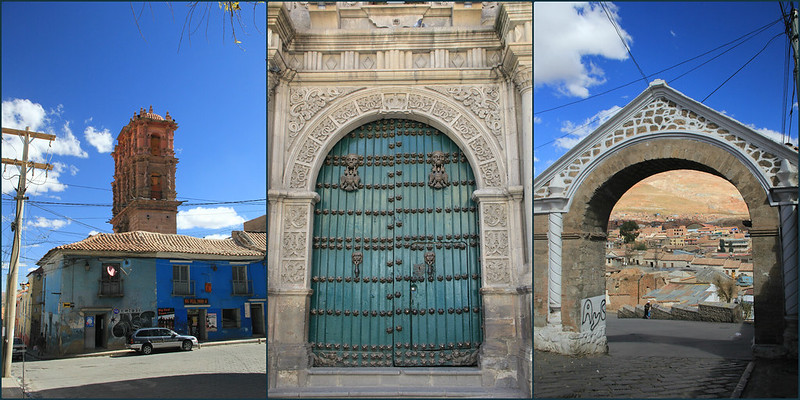

But there’s something incredibly appealing to me about grand colonial buildings that have been left to weather and decay. Something about the intricate detail of their design and the mystery of the past they once embodied.

For that reason – and despite the lack of decent restaurants serving something other than pizza – I knew that Potosí was deserving of more than a fleeting visit in which to take a tour of its mines.

So I booked us into Potosí’s Eucalyptus Hostel for a few nights (which, incidentally was the first hostel on our trip to have central heating in our room; a huge bonus at 4070 metres above sea level in the middle of winter) and set about exploring the city.

Fortunately for us, we’d been at altitude (over 3000 metres above sea level) since we arrived in Huaraz just over two months beforehand, so we were fully acclimatised by the time we reached Potosí. But if you’re not, you may need to interrupt your sightseeing with regular breaks to sip coca tea. This is no bad thing; I’d happily drink the stuff at sea level and am actually completely gutted that it’s illegal here in the UK.

As we took the short walk from our hostel to the centre of the city, we’d pass brightly-painted buildings with ornate wooden balconies overhanging the streets below. We’d notice that a few had been converted into hotels or hostels, with names such as Hostal Colonial or Hostal Carlos V Imperial, hinting at a time when – between 1538 and 1825 – the Spanish colonised the city.

We’d wander aimlessly through the maze of back streets on the outskirts of the city’s historical core, always using the towering cathedral in the Plaza 10 de Noviembre as a landmark to ensure that we didn’t stray too far.

Although it was originally built in the late 16th century, most of what you see of Potosí’s cathedral today is actually a neoclassical construction, following the collapse of the earlier version in the 19th century.

Although we missed the opportunity due to it being closed at weekends, it’s possible to visit the bell tower for some amazing city views (admission B$10).

Potosí is also home to a number of beautiful convents and churches, dating from as far back as 1547, many of which have undergone more recent restoration work to make them what they are today. They stand tall and magnificent in stark contrast to the crumbling, weathered, often graffiti-covered buildings that surround them.

The city’s star attraction (and one of South America’s finest museums) is the National Mint of Bolivia. The first mint was constructed in 1572 under orders from Viceroy Francisco de Toledo, but the existing building – that spans an entire city block – was built almost two centuries later.

It’s now a museum filled with many of the original pieces of equipment and machinery used in the minting process, along with a host of historical treasures, coins, and other silver artefacts.

Visit is by guided tour only, and whilst it’s a little rushed, it’s definitely an interesting and educational experience that I’d thoroughly recommend.

It’s also worth taking a wander north of town along Oruro, to Plaza del Estudiante. Here you’ll find the incredible La Capilla de Nuestra Señora de Jerusalén, an ornate church that stands on the edge of a shaded square where traditionally-dressed locals rest from the heat of the afternoon sun.

There’s also a tiny local market that branches off down one of the little side streets not far away. It’s a part of the city seldom frequented by tourists, so pack your phrasebook, wear a smile, and be prepared to part with a few bolivianos in exchange for a couple of pieces of fresh fruit or a bag of coca leaves.

Alternatively, if you want to get completely off the beaten track, cut across to Calle Quijarro, a narrow, winding residential street, once home to the city’s potters and now known for its hat makers.

The buildings here may not be grand or impressive, but the area is somehow more authentic, more atmospheric – quaint, almost. The doorways are decorated with family crests – a symbol of the city’s affluent past.

Conversely the crumbling stonework and faded paintwork dotted with graffiti illustrate Potosí’s subsequent decline into poverty. Visit at dusk when the empty streets and the fading light of the afternoon sun give the area a sense of mystery and intrigue, and of beauty and abandonment.

By all means come to Potosí to take a tour of its mines, to learn about the lives of workers who spend the majority of their waking hours underground in the hope of finding that elusive vein of silver that will buy them a privileged life above ground.

But don’t leave without also taking a stroll through its ancient streets, lined with ornate churches and colourful, crumbling colonial buildings that offer a very real glimpse into the city’s past. That intriguing mix of successes and struggles, and of grandeur and decay.

Have you visited Potosí before? Is it somewhere you’d like to add to your Bolivian itinerary?

If you like this article, please follow along on Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ or you can look me up on Instagram or Pinterest too!

No Comments