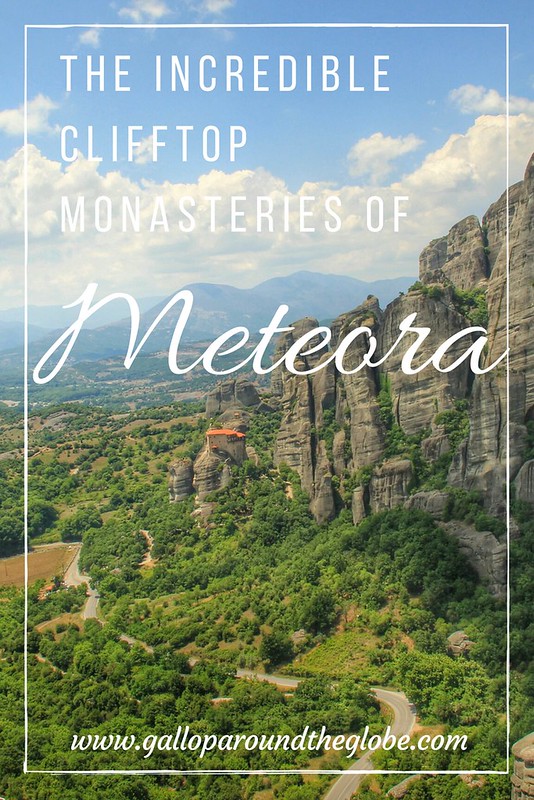

Just like the surreal volcanic landscapes of Cappadocia and the bizarre natural terraces of carbonate minerals in Pamukkale, as soon as I saw photographs of the stunning clifftop monasteries of Meteora, I knew I had to go.

Those of you who are regular readers of this blog will know that I’m an avid photographer and hiker and will literally jump at any opportunity that allows me to combine both of these passions. Meteora offers hiking and photographic opportunities in bucket loads, through landscapes so extraordinary that they have to be seen to be believed.

Monasteries of Meteora | The Creation Story

Meteora is a geographical region in mainland Greece where you’ll find immense towers of sandstone rock, split by earthquakes and weathered by wind and rain over millions of years.

It is estimated that somewhere around the ninth century the first hermits began to arrive in the area, seeking spiritual isolation, and making homes for themselves inside hollows and fissures in the rocks.

Some of the sheer-sided rocks tower almost 600 metres above the plain, so scaling them was no easy feat, especially when the only tools the monks had at their disposal were self-made ropes and ladders.

This ensured that the area remained inaccessible to all but the most determined visitors and intrepid climbers. The monks led a life of solitude, meeting only on Sundays for worship. As more and more monks congregated in the region, a rudimentary monastic state was formed, and by the end of the 12th century an ascetic community had settled in Meteora.

No-one knows exactly when the monasteries were established, but it is estimated to be somewhere towards the end of the 14th century, when the hermit monks were seeking a retreat from the expanding Turkish occupation in an around the fertile plain of Thessalia.

Bearing in mind that the monasteries were constructed using a very basic system of ladders, pulley, nets, and baskets to haul materials up the sheer rock faces, few monks would be fortunate enough to witness the completion of one in their lifetime.

Meteora Today

Of the 24 monasteries originally constructed on the summits of Meteora’s towering rock sculptures, only six remain today. But these six form one of the largest and most important complexes of Greek Orthodox monasteries in Greece (second only to Mount Athos). The monasteries of Meteora are also the second most visited tourist attraction in the country (no prizes for guessing that The Acropolis in Athens is the first).

The name, Meteora, is of Greek origin, literally meaning “suspended in the air” or “in the heavens above” due to the sheer height at which the monasteries stand, isolated from each other and hundreds of metres above the fertile plains below.

Where to Stay in Meteora

The nearest town to Meteora is Kalambaka (pronounced “Kalabaka”; apparently the ‘m’ and ‘b’ together form a ‘b’ sound), but we’d heard that – due to its proximity to the second most visited tourist attraction in Greece – it was horribly touristy, so we decided to base ourselves at nearby (30-40 minutes on the bus) Trikala instead.

We stayed at Hostel Meteora (now ‘Nomads Meteora’), which was situated in a lovely location close to Trikala’s old town and castle, and was cheap; we scored a double room with private bathroom and balcony for just £25 per night.

Whilst Trikala was largely occupied by more locals than tourists, and did have more of an authentic Greek feel to it, getting to and from the monasteries of Meteora was a proper pain in the arse.

The bus times from Trikala to Kalambaka (it’s also possible to catch the train but they run more infrequently and are more expensive) don’t tie in with those from central Kalambaka up to the monasteries. The result of this is that you either have to get up ridiculously early (we’re talking 4am to catch the 5am bus) or you have a good couple of hours to kill in Kalambaka beforehand, which significantly reduces the amount of time you have to explore the monasteries.

I thought that booking a tour from our hostel would remove the logistics of bus travel to Kalambaka (as you normally get collected by minibus from the hostel, and are delivered back to your door), but alas – all tours start from Kalambaka.

In hindsight, if I did it all again, I’d chose to stay in Kalambaka a little out of the centre, or in Kastraki, further up the hill from Kalambaka but closer to the monasteries.

Visiting the Monasteries of Meteora

We had two full days in Trikala, and I had several goals I wanted to achieve within that time:

- Hike the trail from Great Meteoron Monastery to St. Stephen’s Monastery

- Watch the sun set over the monasteries of Meteora

- Explore Trikala’s old town and castle and eat my first Greek salad of the trip

Due to the logistics of the buses back to Trikala, we didn’t think it advisable to stick around for the sunset and then have to try and find our way back down to Kalambaka in the dark and risk missing the last bus home, so we decided to book a sunset tour through our hostel with Meteora Thrones.

The sunset tour would also incorporate a visit to the only monastery that remained open after 5pm – St. Stephen’s Monastery. However St. Stephen’s was also the only monastery to be closed for six days of the week. Fortunately our first full day in Trikala was a Monday – the only day St. Stephen’s Monastery was open to the public.

So we decided to explore Trikala on Monday morning, followed by the sunset tour in the afternoon, and then we’d spend a full day on Tuesday hiking the monastery trail independently.

Sorted.

Except that it wasn’t when those ominous-looking skies arrived, and a thunderstorm began to roll in.

Catching hypothermia and missing the sunset on our ‘Sunset Tour’

There was absolutely no point moving our sunset tour to the following day, because by then we’d already lost half of the full day we needed to hike the monastery trail, so we just tried to stay hopeful and convince ourselves that the skies would clear.

I’ve never had much luck with the weather when it comes to catching sunrises or sunsets over iconic landmarks (failed three times at Angkor Wat and again at the Taj Mahal), so I had already prepared myself for the worst.

On the plus side though, cloud cover offers shade from the direct sunlight that can often over-expose photographs, and helps to better define outlines and highlight colours. It also makes for some moody, atmospheric shots.

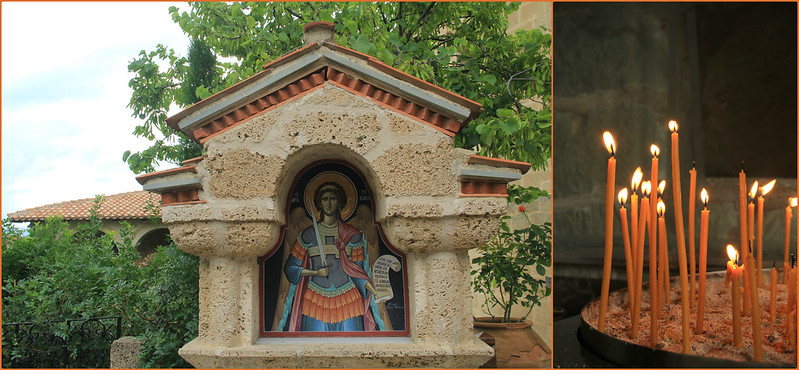

As well as half an hour to look around the grounds of St. Stephen’s Monastery (which – having been inside several – is definitely more worthy of the €3 entry fee than some of its counterparts), our guide showed us some of the caves in which the monks used to live, and took us to all the best viewpoints.

He even pointed out the Holy Trinity Monastery – the most dramatic-looking and least accessible of the six, and one that was used in the filming of the James Bond movie ‘For Your Eyes Only‘.

But then the wind picked up, the cloud cover thickened and the skies grew darker. Stupidly, I’d brought no extra layers (you’d have thought I’d have learned after my experience in the Picos de Europa), so standing out on the rocks waiting for the storm to pass over was giving me hypothermia.

We gave up on our sunset quest when it began to rain, and it didn’t stop raining until the following morning. We had to make the 20 minute walk from the bus stop in Trikala to our hostel in a torrential thunderstorm with a flimsy rain poncho between the three of us – me, Stu and my precious DSLR.

This is the view we were left with as we ran for shelter, but if you’d like to see what it looks like when there’s a proper sunset, check out some of Lawrence Norah’s photographs here.

Hiking the monastery trail independently

The following day we got up super early to catch the bus from Trikala, and had plenty of time to grab a spot of breakfast in Kalambaka before the 9am bus took us up to the Great Meteoron Monastery – the start of our hiking trail.

Great Meteoron is the largest of the six monasteries, and definitely one that’s worth a look inside. It’s at this monastery that you can watch the centuries old rope and pulley system still in place.

The medieval ‘cable car’ is used to transport building materials for restoration, as well as food and water supplies, and the monks – or priests – themselves.

We spent almost two hours exploring and photographing Great Meteoron, so that when we did eventually drag ourselves away, we were starting to hike in the sweltering heat of the midday sun.

The next monastery along, and one that can be seen from Great Meteoron, is Varlaam, named after its founder, Hosios Varlaam.

To ensure that we made it to the end of the trail before dusk, we skipped the interior of this one and continued on to Roussanou. Although it’s probably one of the smallest monasteries inside, Roussanou boasts some beautiful gardens and spectacular panoramic views.

Rickety wooden ladders still hang from the outside of the building – evidence of how the monks used to get themselves and their supplies in and out of the monasteries.

After leaving Roussanou, we climbed some stairs to take us back up on to the road, but part the way up we spotted a tiny little track leading off to the right. In the spirit of adventure we followed it, and were rewarded with this incredible view.

Meteora never failed to surprise and delight me. There are so many hidden viewpoints, and so many different angles from which to photograph the six monasteries, and every time the light changed it offered a slightly different perspective to each shot I captured.

Passing Holy Trinity we continued on to St. Nikolaos Anapafsas, the closest monastery to Kastraki village (just one kilometre away), where I became a little obsessed with capturing the perfect shot of a Greek flag blowing in the warm summer breeze.

Again, the inside of the monastery (at least the section open to the public) is quite small, but venture out to the gardens at the back and you’ll be glad you parted with your €3 for views like these.

By the time we reached St. Stephen’s Monastery, we were desperately in need of some shade and a cold beer. The day had run away with us in a whirlwind of extraordinary landscapes. I didn’t want to leave.

We made our way back down to Kalambaka on a narrow, winding track that passed through woodland and under the shade of trees, the imposing rock faces of Meteora rising above us as we walked.

As we approached Kastrika, and the terracotta-tiled roofs of Kalambaka came into view, we knew that our Meteora adventures were coming to an end. The following morning we would be on a bus bound for Athens, heading back towards the hustle and bustle of city life.

Whilst the prospect of visiting Athens excited me, I could quite easily have spent a whole week exploring the magnificent monasteries of Meteora. Maybe then I would have been lucky enough to capture that elusive sunset photo 😉

Have you visited Meteora? What’s the most incredible landscape you’ve been fortunate enough to witness?

5 Comments

Wonderful article Kiara !!!

Thanks for mentioned Meteora Thrones – http://www.meteoratour.com

Hope to see you back soon !

I’ve heard of Meteroa before, and it just completely amazes me how they built these monasteries at the tops and side of these cliffs/rocks! I would love to see this someday myself, but again, if it involves some serious hiking, then I probably wouldn’t :P. It’s too bad that the weather didn’t hold up for you again! I bet sunset would be lovely over this scenery. But I agree, I like cloudy days for taking pictures the best. And you got some really gorgeous ones!

Don’t worry, it doesn’t involve any serious hiking! If it’s just the six main monasteries you want to see you can easily walk between these on tarmac roads 🙂

The beauty of Meteora is really on a whole different level, isn’t it? Seeing those monasteries perched at the top of the rock pillars is really incredible. I had the chance to visit it during sunset and the view is just spectacular!

Aw, so jealous you were able to catch a sunset there! I’ve seen photos of how incredible the place can look at that time of day (damn weather! ;-)). I’m just glad I was able to visit Meteora at all. Like you say, the beauty really is on a whole different level 🙂