If you’ve read my last post on Arequipa, you’ll know that I chose to spend the afternoon of my birthday wandering around the grounds of a monastery. Although this may sound like a rather odd choice of activity to celebrate the anniversary of one’s birth, my visit to Santa Catalina turned out to be one of the highlights of the three months I spent in Peru.

Not only is Santa Catalina Monastery considered to be one of the most important and prestigious religious buildings in Peru, it is also historically fascinating, structurally intriguing, and visually stunning. Just the photographs alone that I perused online before my arrival into Arequipa were enough to convince me that this was somewhere that I simply couldn’t afford to miss.

A little piece of history

Santa Catalina Monastery was founded in 1580 by a rich widow, Doña María de Guzmán, who was born in Arequipa approximately 40 years prior to the monastery’s conception. She used her wealth and power to create an exclusive society that only the elite were able to enter.

Whilst tradition at the time dictated that the second son or daughter of the family would enter a life of service to the church, only the wealthiest Spanish families could afford the dowry of 2400 silver coins (equivalent to about $150,000 today) for their daughter’s admission to Santa Catalina.

Each nun was required to bring 25 items into the monastery with her and was entitled to her own quarters, together with a personal servant who would cook her meals and wash her clothes.

Metaphorically the streets of Santa Catalina were exactly as the citizens of Arequipa believed them to be – paved with gold.

Enlarged in the 17th century, the monastery occupied an area of over 20,000 square metres and housed approximately 450 people (a third of them were nuns; the remainder were servants) in its heyday.

It was Pope Pius IX who was the catalyst for the monastery’s decline. In the late 1800s he sent Sister Josefa Cadena, a strict Dominican nun, to reform Santa Catalina. The rich dowries were subsequently returned to Europe and all the servants and slaves were freed. The nuns were then given the option to leave, or to retain their residency within the complex. By the mid 1900s just 20 nuns remained.

The monastery suffered structural damage in the 1960s when two powerful earthquakes struck Arequipa. Unable to afford the restorations, the remaining nuns made the decision to open the greater portion of Santa Catalina to the public. Not only would this help to pay for the repairs to the building, but it would also cover the cost of the installation of electricity and running water, which had by then become required by law.

The modern-day monastery

Today Santa Catalina is owned by a private company. This city within a city – hidden behind imposing stone walls two blocks north of the city’s Plaza de Armas – sees up to 500 paying guests each day during high season.

Approximately 20 nuns still live in the northern quarter of the complex, but the rest is open for guests to roam freely as they wish. Whilst the majority of the areas open to the public are now purely ornamental, the laundry area – which is comprised of an inventive system of stone basins fed by water running down a sloped gutter, vegetable garden and adjoining kitchen – is still in use today.

Inside Santa Catalina

The city of Arequipa is guarded by three dramatic volcanoes, so it comes as no surprise that Santa Catalina is built from sillar (the white volcanic rock that gives Arequipa its name of ‘the white city’) and ashlar (petrified volcanic ash from Volcan Chachani).

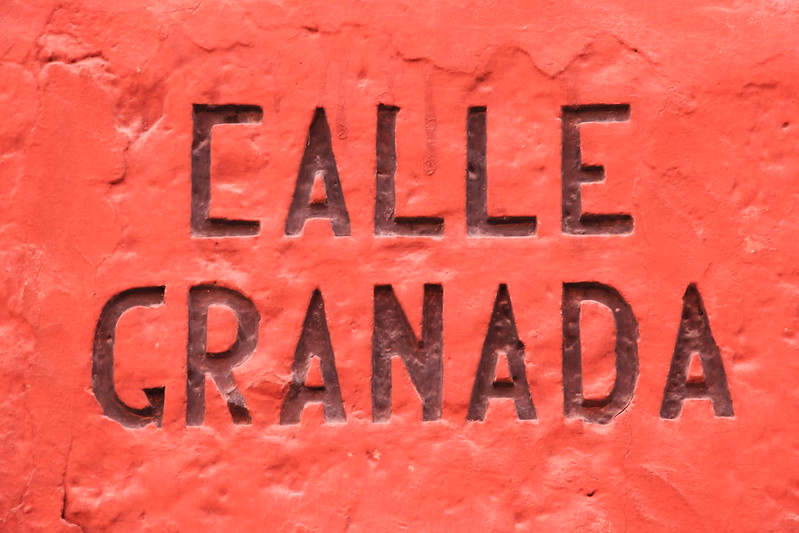

Another unusual feature of the complex is the style in which it’s constructed – known as Mudéjar – which has been adapted by the Spanish from the Moors. There are countless examples of the Mudéjar style of architecture throughout Spain (think the Alhambra (Granada), the Mezquita (Córdoba) and the Alcázar (Sevilla)) but it’s a style that rarely found its way into the colonial buildings of Peru.

Inside Santa Catalina is an inviting maze of narrow cloisters, walled streets, sunny courtyards and cozy living quarters in which you can get wonderfully lost for hours. There is a finely-printed miniature map on the back of your ticket, but in my opinion it’s far better to wander aimlessly and see where your curiosity takes you.

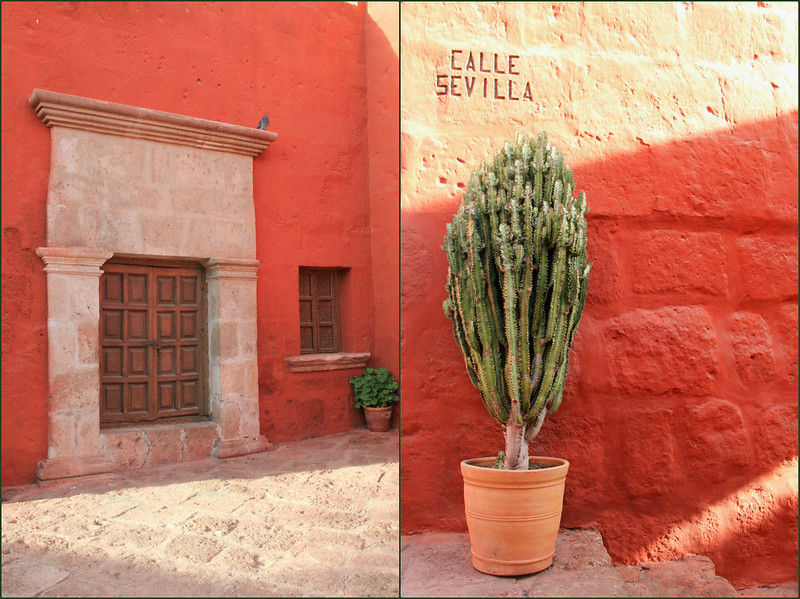

I loved the use of colour within the monastery. The rich blues and burnt oranges were complimented perfectly by the lush green plants, cacti and succulents that were scattered throughout the complex. Considering Arequipa’s isolated location in a fertile valley tucked between desert and mountains, the colours inside the monastery were reminiscent of a Peruvian desert landscape – the hot sun shining down on a horizon of red rocks dotted with prickly pears and set against the backdrop of a deep blue cloudless sky.

There is a church within the complex, along with a number of different chapels and a total of 81 individual houses. The houses are all slightly different in their design, which made exploring each one all the more enjoyable. The bedrooms contain a few of the original pieces of furniture and artefacts, and the soot-stained kitchens are decorated with various cooking utensils that would have been used at the time (whether or not these are originals is difficult to say).

I had a bit of fun with (what I assume to be) a cake tin that had been crafted in the shape of a speech bubble, and we even found a life-sized model of a nun in one of the rooms, who actually looked more like a ghost. Joking aside though, every effort has been made to make Santa Catalina feel like a living, breathing monastery in which it wouldn’t be unusual to see one of the 20 nuns who still live here, pass you along one of its narrow streets.

Even the cafe has been tastefully decorated in keeping with the rest of the monastery, with Moorish-inspired furniture and wall hangings. It’s the perfect place to take a break and reflect upon your surroundings, whilst enjoying a mean espresso and a freshly-baked pastry.

Every room, corridor and courtyard serves its own little purpose in the monastery. There’s the Arco de Silencio, under which the nuns would meditatively pass, clutching their rosary beads and reading their bibles in silence.

Then there’s the Claustro los Naranjos (Orange Cloister), named for the orange trees clustered at its centre that represent renewal and eternal life.

Plaza Zocodober (‘Zocodober’ comes from the Arabic word meaning ‘to barter or exchange’) served as a site where nuns gathered every Sunday to exchange handicrafts such as soaps and baked goods, and Calle Córdova, flanked with rooms that served as living quarters for the nuns, is reminiscent of Calleja de las Flores in Córdoba, Spain, with hanging geraniums at either side.

It’s also interesting to discover that the streets within Santa Catalina Monastery are all named after Spanish cities. Calle Córdova is one of these, along with Calle Sevilla and Calle Granada, to name but a few.

We spent the whole afternoon wandering through the grounds of Santa Catalina, in an attempt to explore every nook and cranny and to photograph every possible detail, and whilst I know there are parts that we missed and details I wish I could have photographed better, I left feeling like we’d given it a pretty darn good shot.

What do you think? What impressions have my photographs given you of Santa Catalina Monastery? Is it somewhere you’d like to go?

If you like this article, please follow along on Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ or you can look me up on Instagram or Pinterest too!

This is part of the #SundayTraveler link-up, hosted by Chasing The Donkey, Pack Me To, A Southern Gypsy, The Fairytale Traveler, and Ice Cream and Permafrost.

No Comments