If you’ve read parts one and two of this four-part series, you’ll know that a tour through Bolivia’s Salt Flats incorporates a helluva lot more than a visit to the largest salt flat in the world and some amusing perspective-skewed shots to take away as a treasured souvenir.

Bolivia’s south-western altiplano is a vast expanse of sparse deserts, mineral-rich lakes, towering volcanos, boiling mud pools, inviting hot springs, and endemic species of plants and wildlife.

On day two we’d explored abandoned settlements, witnessed the colour-changing waters of the region’s mineral-rich lakes, watched bubbling mud boil inside volcanic craters, relaxed in a hot spring and freeze-dried our clothes (unintentionally, mind!), so when I awoke on the (early) morning of day three, I couldn’t wait to see what Bolivia’s remote wilderness had in store for us.

There wasn’t a single cloud in that enormous blue sky as we drove towards the first of four more spectacular lakes. When I began this journey, I never expected to see so many bodies of water in a such a vast expanse of endless desert where hardly anything grows. But Bolivia’s south-western altiplano is full of them, and each one possesses its own unique qualities and is at the same time starkly different to the next.

Considering the sparse amount of vegetation around for them to feed on, I was also surprised that so many animals managed to maintain an existence out here. But we regularly spotted herds of llamas, alpacas or vicuñas, and by the end of day two we’d also been introduced to desert foxes, viscachas (from the chinchilla family) and Rheas (flightless bird, similar to an ostrich).

We’d seen vicuñas previously in Peru, on our hike through the Colca Canyon, and whilst we hadn’t really been able to get any closer to them on this occasion than we had done then (they are wild creatures after all), it was lovely to see so many of these graceful animals in their natural habitat.

You’ll only find vicuñas at altitudes of between 3200-4800 metres above sea level, on the high plains of the Andes, so spotting them is a rare and beautiful treat.

As we approached Laguna Colorada (red lagoon), it was difficult to believe that the colours we were seeing were actually water. Laguna Colorada is a shallow salt lake within the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve, close to the border of Chile, and at first glance you’d think someone had been wreaking havoc with a pot of paint here.

The amazing coloration (which ranges from a rusty red-brown, to burnt orange, to an intense blood red) is caused by sediments and algae in the water. Although we didn’t see too many on our visit, the lagoon is also home to James’ Chilean and Andean Flamingos, the latter being the rarest flamingo species in the world.

In stark contrast the water in the next lake we stopped at was a swirling mixture of rich blues and deep purples. A few flamingos appeared as distant specks on the water’s surface.

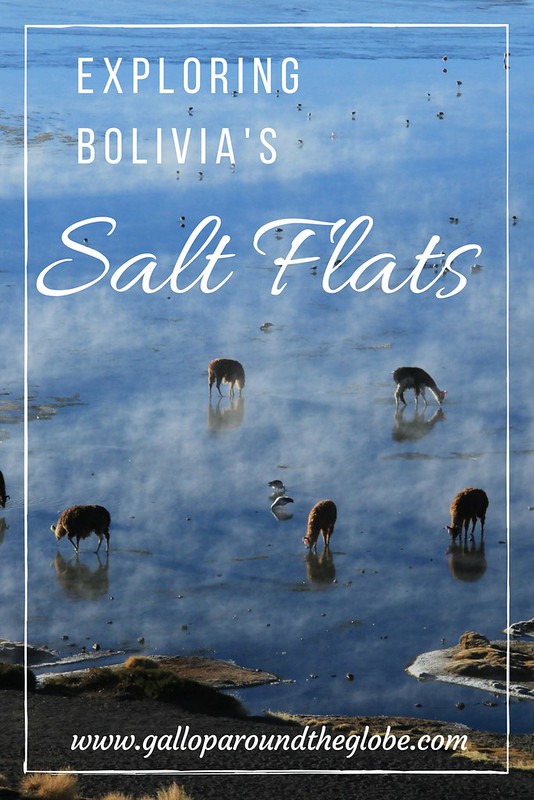

At the third lake we looked down upon a collection of llamas paddling in the shallow waters of the lake’s edge, an atmospheric mist lingering around on the surface of the water.

The fourth lake, Laguna Hedionda, promised a flamboyance (yes that is the actual collective noun, I looked it up!) of bright pink flamingos for us to feast our eyes upon, but before then our driver made a stop at a curiously-shaped rock in the middle of the desert.

This much-photographed rock actually has a name too. Árbol de Piedra (stone tree) is an isolated rock formation that appears to grow out of the altiplano sand dunes of Siloli, its strange shape occurring as a result of strong winds eroding the soft sandstone.

Having snapped a photograph of it, there wasn’t a lot more to hold our interest in the Árbol de Piedra. However there was a much larger rock (or collection of rocks) close by that – if rocks could speak – was inviting us to climb it.

Never one to turn down such a kind invitation, I left my camera with our guide and – sadly with more enthusiasm than competence – followed Stu up the rock face.

What I hadn’t considered when I made my way up (I was too busy thinking about what an amazing photograph our guide would be able to snap of the two of us at the top) was the task of getting down. For those of you who are long-term readers of this blog, you’ll know that I’m not great with heights. I also find ascending a helluva lot easier (and less scary!) than descending.

So, whilst Stu was half the way down, I was still standing at the top trying to figure out exactly how I’d made it up as far as I had, and starting to wish that I hadn’t. Árbol de Piedra was only meant to be a brief stop on our south-western circuit, but I single-handedly ensured that it wasn’t by getting stuck half the way down the rock face, and having to be rescued (thanks Stu!).

I was quite pleased to be stopping at Laguna Hedionda after that. I couldn’t get into too much trouble there.

And there was plenty of flamingo action – exactly as promised.

Although I’m not sure about the authenticity of this pair.

After spending a significant amount of time attempting to sneak up on a few flamingos who had chosen to feast on algae close to the shoreline (my 18-135mm lens is no good for long-distance wildlife photography), we reluctantly hopped back in the jeep and headed towards the location of our day three lunch stop.

And what a location it was.

Valle de las Rocas (Rock Valley) is – as its name suggests – a collection of interestingly-shaped volcanic rocks and boulders that you can ramble over, climb up, hang from, or shelter beneath. We were free to roam to our heart’s content while our cook rustled up one of our best lunches of the entire trip.

Sufficiently fed, watered and exercised, we made our way towards yet another unusual sight – a train track running straight through the Bolivian desert. I learned from our guide that this was one of the first train lines built in Bolivia, connecting La Paz to Villazon, on the Argentinean border.

Can you spot me?

From the railway tracks we slowly made our way towards our accommodation for that evening – a hotel made (almost) entirely of salt.

The aptly-named Hotel de Sal (Salt Hotel) is located on the shores of the Salar de Uyuni, in a little town called Colchani, and has been constructed using blocks of salt extracted from the nearby flats. Even the furniture inside is made of salt, and the beds that we were to sleep in that night. It’s easily the most novel place I’ve ever stayed in.

Apart from the novelty factor of staying in hotel made of salt (coupled with the temptation to lick the walls), what we were all desperately looking forward to at the Hotel de Sal were some hot showers. Aside from our brief soak at the hot springs, we’d not seen any hot water (or any showers) since leaving Tupiza, so a long and thorough wash in some agua caliente was just what the doctor ordered.

Unfortunately our guide had some bad news to break to us. There had been a problem with the water supply or the water-heating system (not entirely sure which or what the problem was; our guide did not elaborate) which meant was that there would not be enough hot water available for everyone to shower at once. We would have to wait for what little water there was to sufficiently heat up, and even then we would only have the use of one out of what should have been about 10 showers altogether.

In order for as many people to get a shower as possible, we formulated a plan.

The first group to arrive would be at the front of the queue, and so on. We would set a 3-minute shower limit and this would be timed. One shower would be in use whilst the next person in the queue would be undressing in the shower cubicle next door. As soon as the first person shouts “done!” and switches their shower off, the second person would switch theirs on.

Yes there was a lot of waiting around, followed by three minutes of fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants showering, but I’m not gonna lie – it worked like a dream.

We were all giving ourselves a pat on the back for co-ordinating such a mission when the dizziness struck.

Assuming it was a result of a mixture of the altitude and of rushing around in a hot, steamy environment, we decided to sit down, relax, open the wine, and wait for it to pass.

But by the time we sat down for dinner I was still feeling faint. Beside me Veerla was looking very pale too and was barely touching her food.

I really started to worry when I looked over at Veerla and her eyes rolled into the back of her head. I stood up to let her through so that she could go outside for some fresh air, but as I did so the room started spinning.

Something wasn’t right.

Veerla and I sat on the ground outside, our heads between our legs, taking deep breaths whilst our boyfriends fetched us glasses of water. We were joined by a few of the others who had been with us towards the front of the shower queue. Whilst no-one had actually passed out, we were all feeling varying levels of dizziness, and it all happened right after we’d queued up and taken a shower.

It was at this moment that Stu (who is a qualified plumber and electrician) pointed out that he’d smelt boiler fumes earlier, coming back into the shower block through an open window. He hadn’t said anything at the time because he assumed they wouldn’t be concentrated enough to do anyone any damage.

One of the gases that is released from a boiler flu, and in higher quantities if the boiler is poorly maintained or dubiously installed, is carbon monoxide.

In an instant it all started to make sense – the reason we had all been feeling faint was because we had been breathing in poisonous carbon monoxide gases. You know, that odourless gas that kills people in their sleep? Yeah, that.

We subsequently ensured that the building was as ventilated as possible (even if it meant running the risk of catching frost bite), and whilst I managed to return to the table and finish my meal, I wasn’t feeling right all evening. At times I was genuinely worried that I’d go to sleep in that big double salt bed of mine, and never wake up.

My solution to that? Stay up as late as possible with our guide and my fellow travellers, drink plentiful amounts of red wine, and brainstorm some crazy photo ideas in preparation for our arrival at the Salt Flats the next day.

By the time I eventually crawled into bed somewhere around midnight, the only thing I was giddy with (aside from the wine maybe) was excitement for the day ahead.

To read the fourth and final instalment of this series, click here.

If you like this article, please follow along on Facebook, Twitter, or Google+ or you can look me up on Instagram or Pinterest too!

PIN ME!!!

14 Comments

Oh my gosh, just when I think Bolivia’s salt flats couldn’t get any prettier, you come out with this post! This one is my favorite so far! That lake with the group of llamas just doesn’t look real. And the flamingos!! The salt hotel is one of the most unique hotels I’ve ever heard of as well, but reading about the carbon monoxide poisoning was scary. I’m glad nothing worse happened!

The whole four days were full of surreal, spectacular landscapes! It really is a truly amazing part of the world 🙂

Wow, was not expecting that turn-for-the-terrifying at the end! Glad everyone was okay. Besides almost getting poisoned, this looks amazing — your photos are incredible. I especially love the llamas in the shallow lake!

Ha! No, neither were we! And yes, it was amazing. Totally lived up to all expectations 🙂 I loved the llamas too. I was actually surprised to find so much wildlife living out in the Bolivian wilderness where nothing grows apart from cactus…

Your pictures are absolutely stunning, the color of the water and how the reflections just shine, exactly how I imagined this place would be!

Regarding the boiler and shower situation, I have the same problem at home… Now I have a detector that makes a horrible noise whenever this happens (the wind pushes the fumes back in from the exhaust pipe, or I have the kitchen ventilator on and oxygen is sucked out of the room), but before, when I did not know what was the reason for it, we even had to call the emergency number once, as me and my husband had horrible headache, dizziness, my husband fainted on the way to the bathroom and we couldn’t figure out what was happening to us. ER also didn’t know, and after reading on the internet for a bit, I found out the “cure” myself. Since I have the detector, now I know how often I actually have this problem at home. Scary.

Oh no, that’s awful you have that situation at home! Where do you live? In England the place would be condemned and considered unfit for habitation until the issue was fixed.

This looks like an amazing trip! I’m dyingggg to go to Chile to see the Atacama desert. I would love to see all of the wildlife there.

Unfortunately I never made it to Chile, but I’d love to explore the Atacama desert too 🙂

I am desperate to visit South America and see the salt flats! But oh my gosh what a scary ending to this post!! I can’t imagine being worried that I would go to sleep and not wake up. I hope everyone was okay and not too shaken by the experience! <3

It was pretty scary for a while until we got the place properly ventilated and started to feel a bit more human. It’s certainly not what you expect at a hotel that regularly hosts tourists!

Your photos made me lol, and I looove the animal shots!

I assume you mean the one of Stu and I doing flamingo impressions? We actually practised those poses for a hilarious 10 minutes before taking that shot! 😉

Thank you for this post! I am heading to Bolivia in October 2017 and your photos and stories are helping me to manage the waiting until then.

I know what you mean, I love reading blog posts about places I’ve booked to visit. But the only problem is it makes me even more impatient to go! 😉 How long are you spending in Bolivia?